I don’t think that computers1 will ever wake up, no matter what software they are running. In this post, I’ll present my version of a lesser-known argument2 for this stance, which I first learned from QRI here3.

The main idea focuses on an aspect of consciousness4 called “global binding”5, which is the deceptively simple observation that we are simultaneously aware of the contents of a moment of experience. In other words, we have a unified experiential “now” with rich structures in it. To make my point, I’ll use a simpler proxy for global binding: the simultaneous experience of two events6.

I’ll show that, under certain assumptions about consciousness, the framework of computation cannot account for simultaneously experienced events. I then discuss the implications of this conclusion, including the possibility that some of the assumptions are invalid.

I try to assume minimal background knowledge in this post, since I believe this argument merits wider awareness.

A Case for Conscious Computers

Why would someone expect a computer to be conscious in the first place?

In case you’re not aware, computational accounts for consciousness are actually in vogue. Their detractors risk being characterized as scientifically illiterate, carbon chauvinists7, or hyperfixated on microtubules8. What makes the proponents so sure that consciousness is a property of computation?

One solid way to conclude that a computer could in principle be conscious goes like this9:

- Consciousness is generated by the brain.

- Physical systems like the brain can be perfectly simulated10 on a computer.

- A perfectly-simulated brain would have the same properties as the original, consciousness included.

There are strong reasons to believe in each of these and they imply that a powerful-enough computer, running the right program, will wake up11.

This conclusion is deeply seductive to technologists. If true, we can understand the brain as a sophisticated biological computer12. If true, we may one day upload our minds onto immortal computational substrates13. And, if true, we might build a conscious AI that’s a worthy successor to humanity14.

The stakes couldn’t be higher!

A Case Against Conscious Computers

The present argument against conscious computers takes aim at #3 above and suggests that no computation, not even a perfect brain simulation, can have a conscious experience.

At a high-level, the argument goes like this:

- Observe that you can consciously experience two events as either simultaneous or not.

- Assume that it’s possible for an analysis of your brain to determine if the events are experienced as simultaneous or not.

- Expect the same for a hypothetically conscious computer (swapping “brain” for “computer”) and find that this assumption (2) fails!

Specifically, we’ll see that no computation can implement the experience of simultaneity. One possible conclusion is that the framework of computation is capable of explaining neither simultaneous experience nor, by proxy, global binding. Without this capability, we must conclude that computation is insufficient to account for our conscious experience.

Alternatively, the argument may contain a bad assumption or logical step, invalidating this conclusion.

We’ll explore both options.

HAL and the Synchroscope

Let’s use a thought experiment to make things more concrete.

Imagine that you and your robot friend named “HAL”15 are watching a fierce lightning storm. HAL claims to be consciously experiencing the storm alongside you. You’ve been deceived by AIs enough times to be skeptical, so you want to verify HAL’s claim.

You wish you had a “consciousness meter” device that you could just point at HAL. Unfortunately, there’s no consensus for how consciousness is physically instantiated (if at all), and so we don’t even have a theory for how to build such a device. You need to be more clever.

After a while, you notice that sometimes two lightning bolts strike simultaneously. Other times, there’s a barely perceptable delay between strikes. You and HAL always agree on whether the strikes are simultaneous or not. Now you want to know: does HAL actually experience the simultaneity, or is it merely reporting it?

You dream of a much simpler consciousness meter called a “synchroscope” that reports whether a visual experience contains two simultaneous bright flashes (e.g. lightning strikes) or not. The design of such a device might not require a full theory of consciousness, since it’s limited to only sensing this one fact about visual experiences. Let’s assume it can be built.

If you point a synchroscope at your brain while watching the storm, you expect it to accurately report whether or not you’re currently seeing simultaneous strikes. It also operates extremely quickly, so there’s no time for it to “cheat” by reading your thoughts after the visual experience.

Do you expect the synchroscope to work on HAL?

Designing a Synchroscope

How might a synchroscope work? What could it measure to determine if the lightning strikes are experinced simultaneously or not? Our only constraints are the laws of physics16.

Your first guess may be that synchroscopes measure events in your brain (e.g. neurons firing) or HAL’s processor (e.g. bit flips) and then infer the simultaneity of the experience based on the simultaneity of these events. However, simultaneity is only defined relative to a measurement frame17 (i.e. it’s observer-dependent). But, we should expect the fact of whether the strikes are experienced as simultaneous to be independent of the measurement frame: what you’re experiencing is independent of who is asking about it! This reasoning makes the simulteneity of events a dubious candidate for informing the synchroscope’s output.

Another option is that the experience of simulteneity is directly encoded in the physical state of the brain/processor. As we just saw, this would have to go beyond the simulteneity of physical events. Perhaps the most promising option is quantum entanglement, which may form rich indivisible wholes and, therefore, could be the objective glue that binds together the different parts of our unified experience18. In this case, the synchroscope might detect two things are experienced simulteneously if they correspond to the same entangled state19. We don’t yet know if the brain leverages entanglement202122 in constructing reality, but we definitively know that HAL does not23.

A third option is that the synchroscope looks at the way information is processed by the brain/processor. This computationalist approach claims that the binding we seek is virtual, so it doesn’t matter how the processing is physically represented. So long as HAL can support the right type of processing, the synchroscope could detect it. And, thanks to computational universality24, we know that HAL (given sufficient memory) can perform any computation that the brain can25.

So, is it even theoretically possible for a synchroscope to work on HAL? The physics-based approaches suggest “no”. However, the computational approach says “maybe, if HAL’s computation has the right structure”. Let’s zoom into this option and see if it’s viable.

Computational Structure as Seen by a Synchroscope

What structure in HAL’s computation could implement the experience of simultaneous lightning strikes? If we can find this, then we could design a synchroscope to detect this structure.

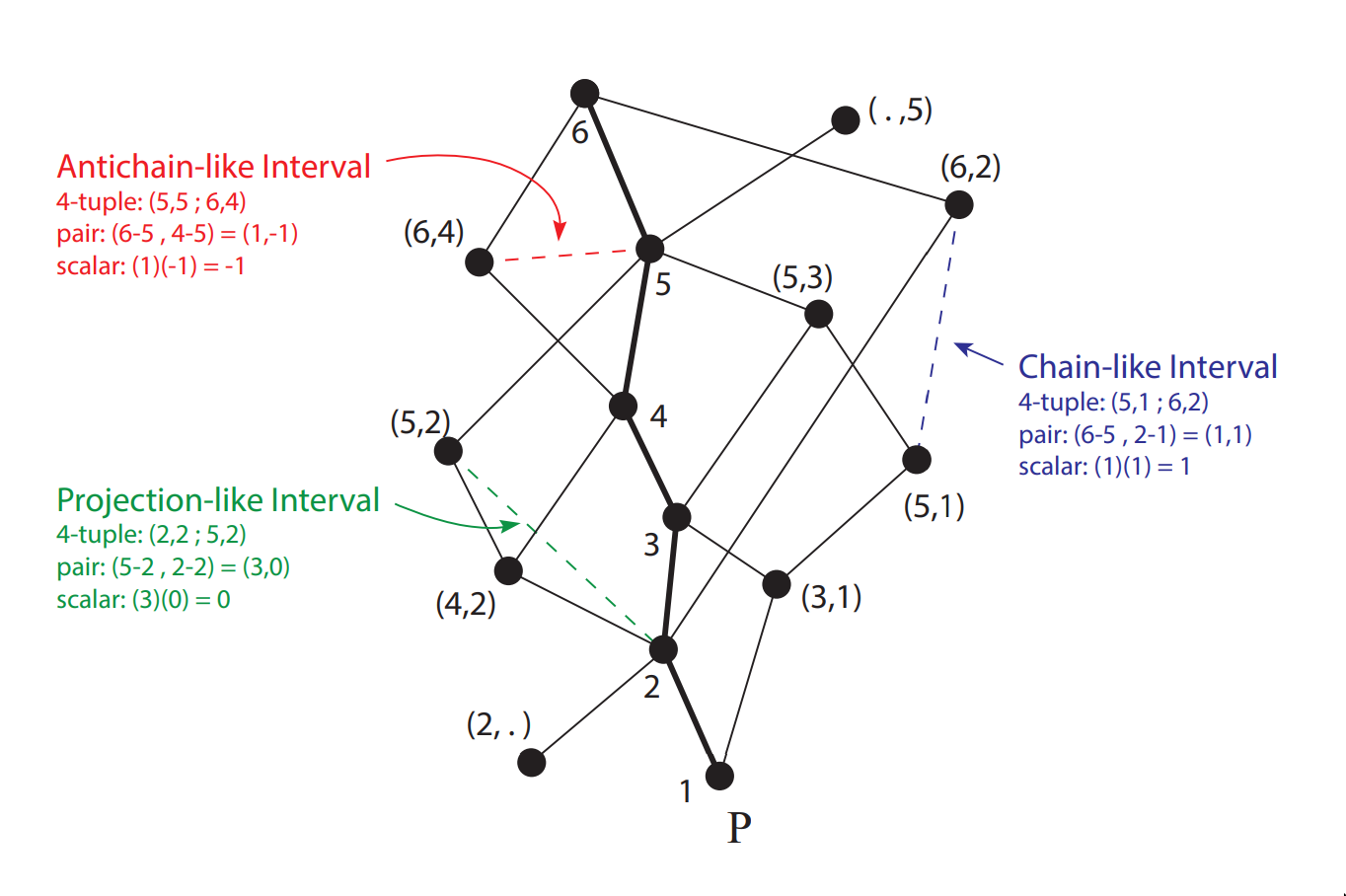

This is tricky because there are several competing theories26 about how to map computational structures to conscious experiences. Also, consciousness aside, it’s not even clear how to think about a computation’s structure: a function can be computed by different algorithms (e.g. bubble or merge sort), algorithms have multiple implementations (e.g. serial or parallel), and these implementations can run on many different physical substrates (e.g. silicon or wood)27. Each of these different levels28 tell different stories about what’s happening during a computation.

Let’s think carefully about how a synchroscope measures a computation. In all cases, the computation must exert a causal influence on the synchroscope. This suggests the causal structure of a computation is a relevant representation: if there’s something not captured in the causal structure then, by definition, it can’t affect the output of the synchroscope and is therefore irrelevant. As we’ll see, the ability for a causal structure to represent simultaneous experiences can be analyzed without committing to a specific computational theory of consciousness.

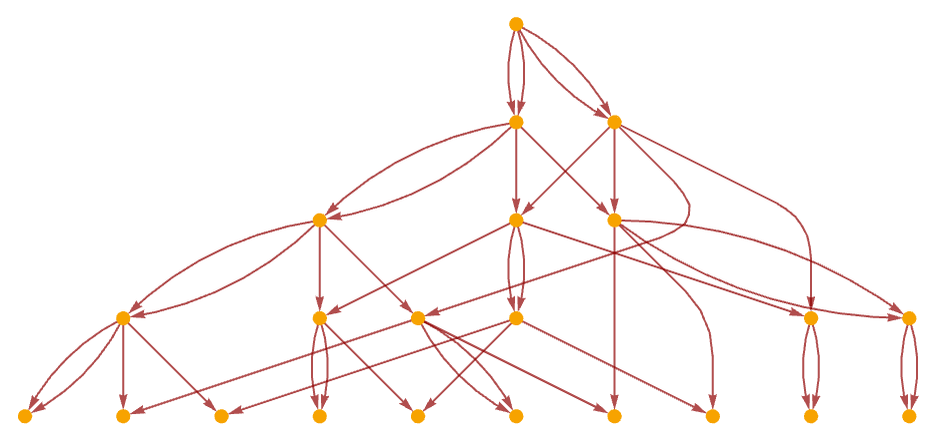

How can we represent a computation’s causal structure? It’s commonly represented as a graph, where the nodes represent simple events (e.g. bit flips) and the directed edges represent causal dependence between these events29. This causal graph is invariant to changes in details like the physical properties of the computer, how information is encoded, and the order of causally-independent events30. It captures the relevant essence of the computation by removing everything the synchroscope can’t measure or infer31.

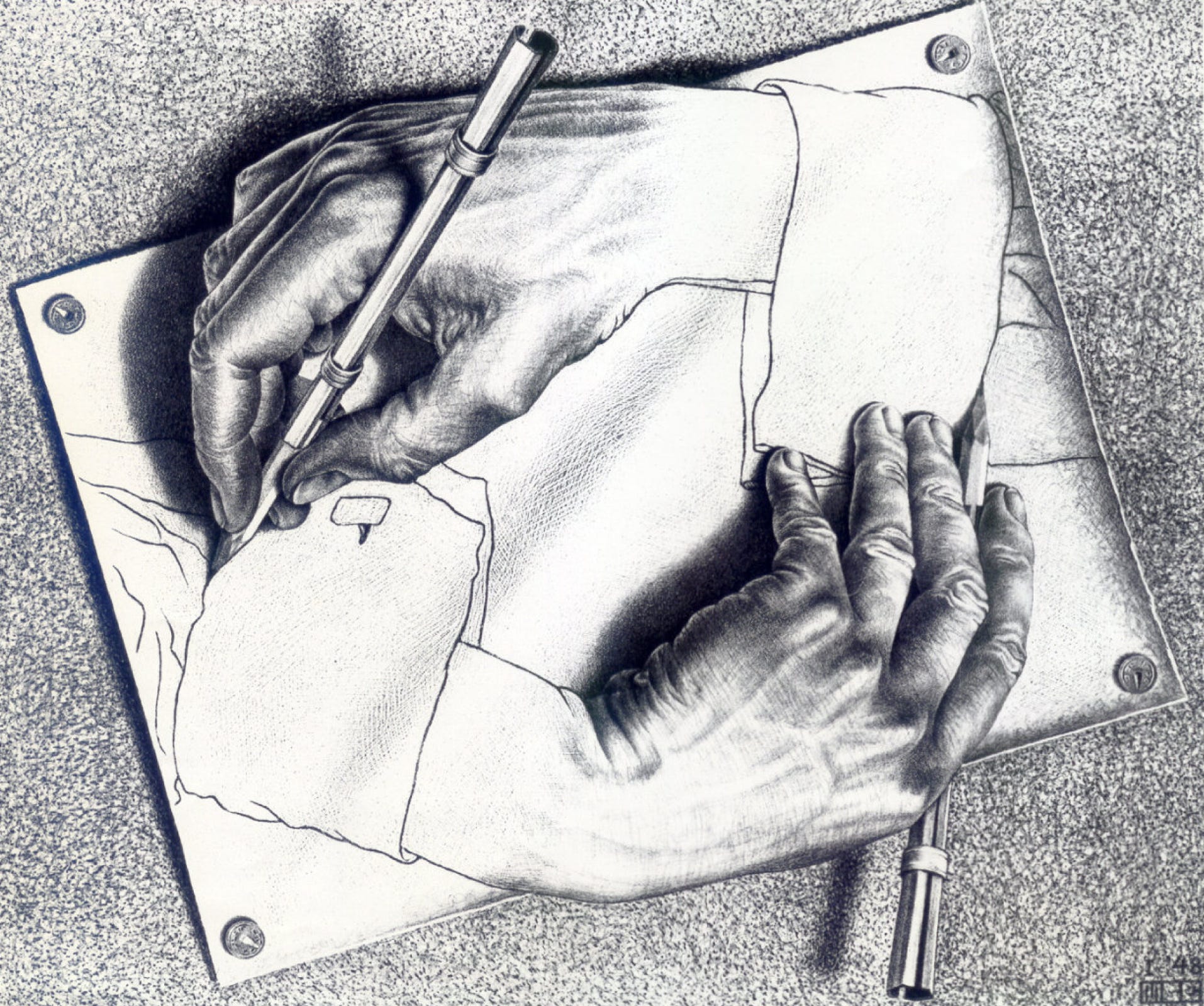

Another reason to consider the causal structure comes from taking an internal perspective on a computation. Imagine an AI exploring a self-contained virtual world. Notice that it can never determine, for example, if it’s running on a CPU or GPU. That’s because it can only infer the virtual world’s causal structure from its observations, and the same causal structure can be implemented by many different physical computers. The same argument applies to an AI building a model of another AI’s hypothetical consciousness: only the causal structure is available!

Causal Graphs Can’t Bind

Let’s assume that the causal graph is all that the synchroscope can know about HAL’s computation. We’ll also assume that the synchroscope knows32 which events in HAL’s causal graph correspond to the sub-experience33 of each lightning strike.

Can the synchroscope determine if these events belong to the same moment of HAL’s experience, using only the causal structure?

We can immediately rule-out any approach that relies on assigning times to the events in the graph. That would require specifying a measurement frame, which is external to the graph’s structure. As previously discussed, this is also in conflict with the observer-independent nature of the how the subjective experience is bound: there simply are no objective timestamps to assign!

A more promising idea is to define some internal frame in the causal graph, relative to which simultaneity can be defined. This is a key idea in Observer-Centric Physics and Wolfram Physics. The issue with these approaches is they only sharply define simultaneity relative to a single event in the graph. So, the entity that “experiences” the simultaneity is itself just a bit flip! That’s not a very rich perspective to take.

A final set of approaches make an appeal to complexity: maybe a sufficiently tangled causal graph will have an emergent notion of simultaneity relative to some (rich) internal perspective. I think these will always suffer from a bootstrapping problem. To group causal events together as “simultaneous”, we first need to define an internal reference frame. But, any such reference frame must itself be made of a group of causal events! We have an infinite regress.

My take-away is that causal graphs simply don’t have the necessary structure to objectively group multiple events into the same conscious experience.

Note: this post is a work-in-progress. The sections below are still being revised and are largely AI-generated drafts.

Back to the Storm

So, can the synchroscope tell you whether HAL genuinely experiences two lightning strikes as one moment?

Let’s recap what we tried. We looked for three possible sources of an objective “same experience” fact:

The timing of physical events (bit flips, neuron spikes). This fails because simultaneity of events requires a reference frame. Different observers can disagree about which events are simultaneous. But your experience shouldn’t change depending on who’s measuring you.

The physical state itself (e.g. an entangled quantum state). This could work for a substrate that genuinely supports objective “wholeness,” but HAL is a classical computer. By definition, classical computers don’t use entanglement in how they process information.

The computation’s causal structure. This is the computationalist’s best hope, but we just saw that bare causal graphs don’t provide a frame-free way to group multiple events into the same experiential “now.”

If you point the synchroscope at HAL, it can only work with HAL’s causal graph. And there simply isn’t a frame-free fact in that graph that says “these two sub-events belong to the same experience.” The synchroscope would have to guess, or cheat by reading HAL’s outputs after the experience, which defeats the purpose.

The synchroscope can’t verify HAL’s claim.

How About the Brain?

You might notice a problem. If we decompose the brain into a causal graph of minimal events (e.g. individual neuron firings), doesn’t the same argument apply? The brain’s causal graph would be just as unable to ground objective simultaneity as HAL’s.

And yet, we do seem to experience simultaneity. So something has to give. There are a few options:

The causal graph decomposition misses essential physics. Maybe the brain’s substrate includes some form of objective wholeness that can’t be captured in a graph of discrete events. Quantum entanglement is one candidate: an entangled state is genuinely one thing, not a collection of separate parts34. If the brain leverages such states, a synchroscope aimed at the brain might have a real, frame-independent “binder” to detect. Whether the brain actually does this is an open empirical question353637.

The causal graph is the wrong level of description. Perhaps converting any physical system to a minimal causal graph necessarily loses the information relevant to experience. This would mean that computational descriptions systematically underdetermine consciousness, regardless of the substrate.

The objectivity assumption is wrong. Maybe there is no frame-independent fact about whether two sub-events are co-experienced. If so, expecting a synchroscope to deliver one is a category error. This rescues computationalism, but at the cost of giving up realism about phenomenal structure.

Each of these options breaks the symmetry between HAL and the brain in a different way. Which one you favor determines your stance on conscious computation.

Ways Out

Let’s be fair and consider the strongest objections to the argument.

”Just add a clock.” One could give HAL a global oscillator or phase code so that a controller marks certain events as simultaneous. But this only achieves coordination, not objective unity. You get synchronization by fiat, not a frame-free fact about binding. The synchroscope would be reading an engineering choice, not a property of experience.

”Define simultaneity from the inside.” Observer-centric approaches (like those in Knuth’s framework or Wolfram Physics) define simultaneity relative to an internal chain of events in the causal graph. This does yield a notion of “now,” but only relative to a chosen perspective. The “entity” experiencing that perspective is itself just a chain of events, so the unity belongs to a particular vantage point, not to the whole system. This is useful for modeling, but thin ice for grounding objective binding.

”Simultaneity in experience is a gradient, not a binary.” Maybe what we call “simultaneous” is just a judgment made within a psychophysical time window. If there’s no sharp fact about whether two events are co-experienced, then the synchroscope was chasing a binary where nature only offers a gradient. This blunts Step 1 of the argument. It’s a coherent position, but it requires accepting that there’s nothing it’s objectively like to experience two things “at once,” which strikes me as a significant concession.

”Put binding in physics.” Allow objective wholeness (e.g. entanglement) to be the binder. Then the synchroscope is a holism-detector: it works on substrates that support genuine physical wholeness and fails on those that don’t. This cleanly separates brains from GPUs, but requires that the relevant holistic structure is real and robust in brain tissue. This is precisely what skeptics doubt on decoherence grounds38, and what proponents attempt to repair.

”Enrich computation.” You can add non-graphical structure to “computation” (continuous fields, intrinsic metrics, etc.) until it can ground a canonical “now.” But at that point, you’ve conceded that bare computation, captured by causal graphs, wasn’t enough. You’re doing physics, not computer science.

None of these escapes is free. They either weaken the claim (“binding is just useful coordination”), relocate it (“binding lives in physics, not computation”), or revise a premise (“there’s no objective fact to read off”).

Closing Thoughts

The lightning storm thought experiment was meant to keep us honest. If there’s a frame-independent fact that two sub-events are co-experienced, where does that fact live?

Not in the simultaneity of physical events, which is frame-dependent. Not in a classical machine’s state, which has no built-in wholeness. And not in a computation’s bare causal graph, which has no canonical grouping.

This leaves us with a few live options:

If you’re a realist about binding, you might conclude that unity is an objective physical property, a kind of wholeness that classical computation fails to capture. On this view, even a perfect brain simulation would miss something about experience, much like a classical simulation of a quantum computer fractures a single quantum state across an exponentially large classical description.

If you’re a computationalist, you might try to enrich “computation” with additional structure (intrinsic metrics, observer-indexed foliations, etc.) until it can ground the unity we report. But this starts to blur into physics. The more structure you add, the harder it becomes to maintain that consciousness is “substrate-independent” in any interesting sense.

Or, you might take the deflationary route and argue that the “simultaneity in experience” premise was too crisp to begin with. What we really have are graded judgments within temporal windows. If so, the synchroscope was a mirage, and the argument doesn’t get off the ground.

Personally, I think the first option is the most promising. The idea that consciousness requires some form of physical wholeness, perhaps quantum entanglement, is pursued by QRI and others39. If true, it would provide a solution to the binding problem40 and might even explain why biological evolution favored bound conscious states: wholeness could come with a computational advantage similar to the advantage we find in quantum computers41.

This doesn’t necessarily imply that physics has non-computable properties42. Instead, it may be that even perfect simulations fail to capture certain properties of what they simulate. The map is not the territory, and maybe the “wholeness” in the territory gets inevitably lost in a computational map.

So: don’t cry for HAL. He was never going to wake up.

Acknowledgements

Thank you Andrés Gómez Emilsson @ QRI for introducing me to these ideas. Thank you Joscha Bach for provoking me to write them down.

Related

- The View From My Topological Pocket: An Introduction to Field Topology for Solving the Boundary Problem

- Solving the Phenomenal Binding Problem: Topological Segmentation as the Correct Explanation Space.

- A Paradigm for AI Consciousness – Opentheory.net

- Computational functionalism on trial

- Non-materialist physicalism: an experimentally testable conjecture.

- Universe creation on a computer

Footnotes

By “computer”, I mean Turing Machines and their close cousins. This includes CPUs and GPUs, but doesn’t include quantum computers.↩︎

Scott Aaronson has aggregated many other arguments against consciousness being a type of computation. My favorite is the question of whether an encrypted form of a computation can be conscious, since it looks random to anyone without the key!↩︎

I believe David Pearce was the first to make Andrés @ QRI aware of this argument.↩︎

“Consciousness” in this post it defined as “what it’s like” to be like to be something. See intro here.↩︎

From the QRI Glossary: “Global binding refers to the fact that the entirety of the contents of each experience is simultaneously apprehended by a unitary experiential self…”↩︎

This isn’t a perfect proxy, since binding might also have small extension in time.↩︎

Think humans are superior to AI? Don’t be a ‘carbon chauvinist’ - The Washington Post↩︎

This theoretical version of computational functionalism is discussed in Do simulacra dream of digital sheep?.↩︎

A perfect simulation assumes sufficient computational resources and perfect knowledge of initial conditions (practically impossible). It must compute the same transformations on (representations of) physical states that we expect from reality (i.e fundamental physicical laws). Our present understanding of quantum theory restricts such simulations to only producing outcome probabilities for a given measurement frame.↩︎

This reasoning doesn’t imply that near-term AI systems will be conscious - it just suggests that computers aren’t missing something fundamental to support consciousness.↩︎

From 2001: A Space Odyssey↩︎

Here we snuck in the assumption of physicalism: that conscious states can be explained within the framework of physics.↩︎

If this is confusing to you, don’t feel bad. It literally took an Einstein to expell this notion of absolute time from physics! See the relativity of simultaneity.↩︎

See Non-materialist physicalism: an experimentally testable conjecture by David Pearce.↩︎

This may be practically impossible, since fully measuring quantum states requires measuring many identical copies of the same system.↩︎

See Testing the Conjecture That Quantum Processes Create Conscious Experience by Hartmut Nevin et al.↩︎

One idea is that nuclear spins can support biologically-relevant entangled states.↩︎

Max Tegmark famously estimated that quantum superposition could only last _ in the environment of the brain.↩︎

Again, we’re assuming HAL is a classical computer (i.e. not a quantum computer), like a CPU or GPU. By definition, classical computers don’t use entanglement in how they process information.↩︎

Turing Completeness Wiki TODO↩︎

Assuming Roger Penrose is wrong about the brain using non-computable processes.↩︎

IIT, … TODO↩︎

TODO Marr’s levels.↩︎

The open philosophical debates about how to think about causality are not relevant here. There is no ambiguity about how to generate a causal graph from a computation.↩︎

Permutation City by Greg Egan takes this concept to a beautiful extreme, demonstrating the absurd conclusions one must accept under computational accounts for consciousness.↩︎

Here we focus only on the causal structure of the information processing, not the underlying physical computer. This is because we previously ruled-out the synchroscope using HAL’s physical state for its operation.↩︎

This is a huge given, since it corresponds to solving the Hard Problem of Consciousness.↩︎

Note that it’s strange to even talk about different parts of the same experience, potentially indicating that experience is not made of parts!↩︎

See Non-materialist physicalism: an experimentally testable conjecture by David Pearce.↩︎

See Testing the Conjecture That Quantum Processes Create Conscious Experience by Hartmut Nevin et al.↩︎

One idea is that nuclear spins can support biologically-relevant entangled states.↩︎

Max Tegmark famously estimated that quantum superposition could only last _ in the environment of the brain.↩︎

Max Tegmark famously estimated that quantum superposition could only last _ in the environment of the brain.↩︎

See Non-materialist physicalism: an experimentally testable conjecture by David Pearce.↩︎

See the “Binding/Combination Problem” or the “Boundary Problem”. See Chalmer’s exposition here.↩︎

For a simple concrete example of how the wholeness of an entangled state lifts the power of a computer from one complexity class to a stronger one, see Computational power of correlations by Anders and Browne.↩︎

Non-computable physics being necessary to explain consciousness was famously proposed by Roger Penrose in The Emperor’s New Mind.↩︎